The Women Who Set Foundations for Our Hancock Whitney History

In Hancock Whitney’s history, two Victorian era women who dared to think well beyond the gender-specific social order of their day were central figures in securing the roots that ensured our founding.

6 min read

-SQ.jpg)

Paul Maxwell

March 1, 2023 |

From legendary queens of ancient empires to today’s top female executives, women have been powerhouses driving success for many institutions across the ages. In Hancock Whitney’s history, two Victorian era women who dared to think well beyond the gender-specific social order of their day were central figures in securing the roots that ensured our founding.

Maria Louise Morgan Whitney, the grande dame of one of New Orleans’ most prominent families, and Agnes Theresa Phillips, a 20-something Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, businesswoman and socialite with ties to New Orleans, were almost 50 years apart in age. Each woman, however, had the savvy to know what her community needed to stay strong. Local people looked to them as leaders in business, philanthropy, and society.

When a turn-of-the-20th-century Gulf Coast economic boom brought about the need for banks built to serve and last, both women became integral in those efforts. In 1883 Maria Louise used proceeds from the sale of her father’s railroad to enable her sons to create the Whitney National Bank. Sixteen years later, Agnes was the sole female among 19 original subscribers establishing the Hancock County Bank.

Through their accomplishments in the midst of a man’s world, both women became directly instrumental in orchestrating the start of the two organizations that grew into Hancock Whitney.

Setting the Stage

In the late 1800s, New Orleans was teeming with opportunity sparked by the World Cotton Expo of 1884, growing industry, expanded passenger railways, and increased trade at the Port of New Orleans. South Mississippi flourished with an influx of tourists, a lucrative timber export trade through the Port of Gulfport, a successful seafood industry, and fertile agricultural fields.

The Mississippi Coast was also fast becoming “the Newport of the South,” a resort and summer residential destination for Northeasterners escaping brutal cold and New Orleanians seeking relief from summer heat and city hustle. Luxury hotels, “shoo-fly” gazebos around old oaks, and sprawling “cottages”—some 10,000 square feet or more—overlooked the waterfronts.

In particular, Bay St. Louis in Hancock County was emerging as almost an eastern offshoot of the Crescent City. Commuter trains linked the two locales for business folks and influential families. People journeyed to and from daily, often spending extended periods in the city and in “The Bay.” Commerce and opportunity surged.

The time was right for new banks to help people manage their prosperity.

Maria Louise Morgan Whitney

Maria Louise Morgan (a.k.a. Mary or Marie) was born in 1832, the youngest of wealthy entrepreneur Commodore Charles Morgan’s five children. Connecticut-born Charles Morgan was a self-made railroad and shipping magnate who moved from Texas to New York at age 14. Finding his fortune in steamships, then in railroads, Morgan ultimately rose aside the likes of Cornelius Vanderbilt as a major player in America’s shipping business. His success in connecting rail lines and Gulf South ports made him even richer.

In 1853 Maria Louise married Charles A. Whitney, the New York agent for Charles Morgan’s U.S. Pacific Mail steamship line. Young Whitney eventually moved Maria Louise and their family South to serve as Morgan’s New Orleans agent. Maria Louise, Charles, and their three sons—Charles Morgan, Morgan, and George Quintard Whitney—lived in a Second Empire mansion on New Orleans’ prestigious St. Charles Avenue, a Garden District residence which their contemporaries felt epitomized the “new” New Orleans.

Grandeur in the Garden District. Maria Louise Morgan Whitney led business, society, and community service from a stately family home at 2233 St. Charles Avenue. The mansion was demolished in 1940.

Commodore Morgan died in 1878, leaving his daughter and her husband significant shares of Morgan’s Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company. Charles A. Whitney, who administered Morgan’s estate, became president of that company. Unfortunately, he would outlive his father-in-law by only four years.

Following her husband’s death, Maria Louise sold her father’s railroad business to fund a new venture for her sons, the founding of Whitney National Bank in 1883. Maria Louise along with sons George Q. and Charles M. Whitney were among the bank’s first directors.

Though her parties and travels made New Orleans social news, Maria Louise was far from a lady of leisure. She was an astute businessperson and noted philanthropist. The “Woman’s World and Work” column in New Orleans’ The Daily Picayune regularly featured her role in the city’s growing economy. The paper also reported regularly on her extensive work to improve the lives of women.

New Orleans Icon. The Daily Picayune often featured Maria Louise Morgan Whitney for her charitable work in New Orleans.

In 1887 Maria Louise gave the then enormous amount of $10,000 to help establish the Christian Women’s Exchange, which was New Orleans’ first free-circulating library, first day nursery for working mothers with young children, a literary and vocational school for young women, an employment bureau, and a shelter for homeless women. At the time, Maria Louise’s contribution was one of the largest charitable gifts from a woman in her own name in New Orleans.

She joined several other prominent women in 1906 in petitioning the state of Louisiana to fund higher education for women, stating, “Are not the girls of Louisiana as much entitled to the benefits of higher education as the boys?”

When Maria Louise Morgan Whitney died on January 5, 1908, she controlled a greater part of the fortune left by her late father. She had founded one of the city’s most storied financial institutions. Her prolific support of cultural endeavors helped make sure fine arts thrived throughout the city. Giving vast amounts of time and money, she had also helped countless women make better lives for themselves and their families.

Agnes Theresa Phillips

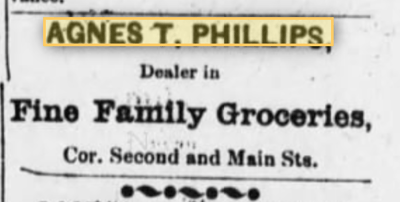

Born in 1878 to Irish parents, Agnes Theresa Philips was already an important business and social leader in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, by the time she was in her early twenties. She was a merchant, the owner of a “fine family groceries” store at Second and Main streets.

Business in the Bay. Unusual for a young woman of her time or social standing, Agnes Phillips was a successful merchant by her early twenties.

Agnes split her time between Bay St. Louis and New Orleans as Bay St. Louis was emerging as a thriving health resort, fishing village, and summer sanctuary for the region’s elite. She saw Bay St. Louis’ first Mardi Gras in 1896, witnessed the town’s first telephone service in 1899, and spent time with a favorite aunt, Eliza Ramond.

Aunt Eliza was the second wife of Peter (formerly Pierre) Ramond, who had come to Bay St. Louis as part of a small group of Brothers of the Sacred Heart sent to establish St. Stanislaus College in 1854. After serving in the French army, Peter had taken temporary vows to serve the church. He fought in the Civil War, returned to Bay St. Louis, and retired from the church to marry. In her later years, Aunt Eliza lived with Agnes and her family.

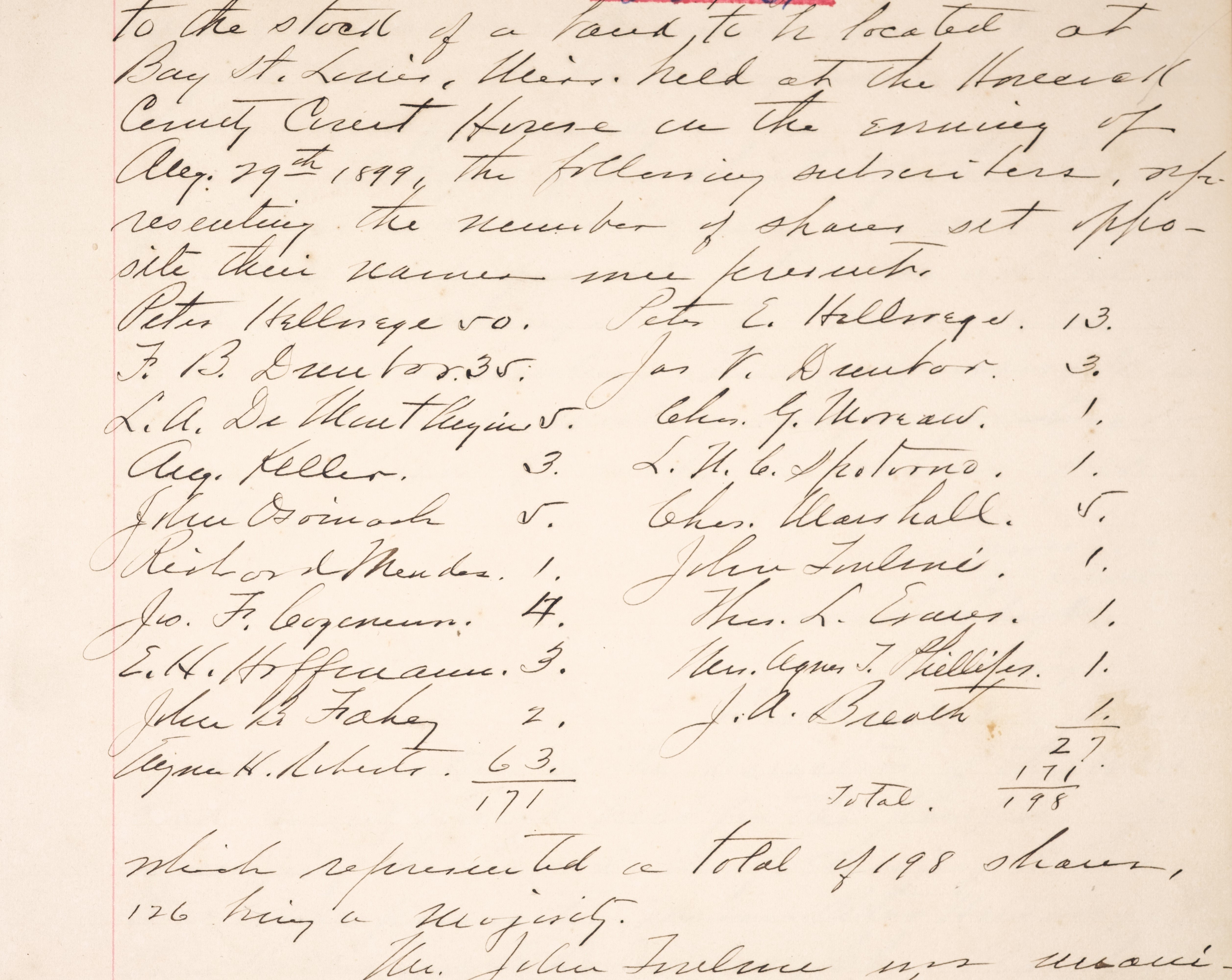

As a new century dawned, Agnes joined 18 men as founding shareholders of the new Hancock County Bank on South Beach Boulevard in Bay St. Louis. The Daily Picayune deemed the opening of the bank “… a progressive movement which will be of inestimable value to Bay St. Louis and materially assist in building up and advancing the interest of this part of the Gulf Coast.”

A Woman of Distinction. Miss Agnes T. Phillips distinguished herself as the only woman among 19 Hancock County Bank founders to sign the bank’s 1899 board of directors ledger.

Just a few months after the bank’s founding, Agnes married Daniel Kinsella at Our Lady of the Gulf Catholic Church in Bay St. Louis. Kinsella, also of Irish descent, came to Bay St. Louis from New York. His brother had married Agnes’ sister Emma. The Biloxi Herald called Agnes and Daniel’s wedding “a notable society event.” The Daily Picayune heralded both the occasion and Agnes’ business prowess, lauding her as “… possessing rare business qualifications” and “…known as a power in the business world.” Agnes and Daniel lived in New Orleans for several years and had six children. Agnes later resided in Covington, Louisiana, before relocating to Chicago after Daniel died.

Agnes Theresa Phillips Kinsella was ahead of her time. She became a merchant when few young women of her refinement chose to step into the retail arena. She carried on a successful business that contributed to the ongoing evolution of Bay St. Louis as a center of economic, social, and residential activity. She defied societal boundaries as the one woman joining much older men to invest in a new bank that would better her community.

Saluting a Legacy

Hancock Bank and Whitney Bank merged in 2011. That transaction brought historical and community connections between the two banks full-circle. Before earlier officers at both banks expanded those ties, however, two extraordinary women helped make our history happen.

Maria Louise Morgan Whitney and Agnes Theresa Phillips likely traveled in similar Gulf Coast social crowds. They probably knew many of the same movers and shakers in a changing world in which women were starting to take their stands and good, solid banks could and would make a difference for everyone. They may have even had tea together, perhaps talking business and community service.

To be sure, they were strong, smart, confident, capable women of vision who embodied the core values at the heart of who we are since Maria Louise and Agnes helped open our doors. With their fellow founders, they laid the foundations for the largest financial services company headquartered in Mississippi, Louisiana’s largest local bank, and one of America’s strongest, safest banks—Hancock Whitney.

We salute Maria Louise, Agnes, and generations of Hancock Whitney women who have led and served tirelessly to foster success for our clients, our communities, and our company.

Explore more Insights

Get financial insights delivered to your inbox

Sign up to receive regular updates from our team of experts.